Honey processing became closely associated with Costa Rica in the late 2000s. Following a significant earthquake in 2008, the Costa Rican government imposed water usage restrictions, prompting coffee producers to innovate their processing methods.

From this necessity, honey processed coffee emerged. Known for its intense sweetness, pronounced body, and complex flavor notes, this processing method quickly attracted the attention of specialty coffee buyers, leading to increased demand.

Today, honey processing is considered one of the big three methods, alongside washed and natural processes. Producers have experimented with varying levels of mucilage retention on the beans to create a range of flavor profiles, resulting in the black, red, yellow, and white honey processed coffees we are now familiar with.

In recent years, novel and advanced processing methods have emerged, allowing producers to differentiate their coffees with unique and unconventional tasting notes. As these techniques have gained popularity, honey processing has become more commonplace and is sometimes viewed as less exciting compared to methods like anaerobic fermentation and carbonic maceration.

However, producers continue to innovate with honey processing. To learn more, I spoke with Jorge Raul Rivera, a three-time Cup of Excellence-winning coffee producer in El Salvador, and Jamie Treby, coffee strategist at DRWakefield.

The Rise of Honey Processing in the Coffee Industry

Certain coffee origins are closely linked to specific processing methods. Brazil is renowned for its natural processed coffees, while washed coffees are particularly popular in Kenya.

Costa Rica pioneered honey processing, developing it out of necessity after government-imposed water usage restrictions in the late 2000s.

Costa Rica is the most well-known origin for honey processed coffees, particularly with the different colors of honey, says Jamie Treby, a coffee strategist at green coffee trader DRWakefield. There are farms that talk about innovating as far back as the early 2000s.

Borrowing from the pulped natural processing used in Brazil, the honey process gets its name from the sticky mucilage left intact on the beans as they dry. Unlike washed coffees, where the skin and pulp are entirely removed, and naturals, where the entire cherry dries intact, honey processing lies somewhere in between. Cherries are pulped to remove the outer skin, leaving behind the mucilage.

Producers then leave varying levels of mucilage intact as the coffee dries, creating different flavor profiles and textures. The different colors imply different percentages of mucilage left on the beans before drying. Typically, the higher the amount of mucilage, the more sugars will be present as the coffee dries, leading to sweeter flavors.

The most common types of honey processed coffees are:

Black honey - 75 to 100 percent mucilage, most similar to natural processing

Red honey - 50 percent mucilage

Yellow honey - around 25 percent mucilage

White honey - around 10 percent mucilage, akin to a washed coffee

Growing Demand

Initial responses to honey processing were skeptical, with some claiming the flavors were too wild or unclean. However, as consumer demand changed, interest in honey processed coffees grew.

More specialty coffee roasters began sourcing honey processed Costa Rican single origins, helping to establish the country's global reputation. These coffees also performed well at auctions, receiving high scores and fetching high prices.

Over time, producers in other countries started to experiment with honey processing.

Graciano Cruz, a pioneering producer from Panama, brought honey processing to El Salvador, says Jorge Raul Rivera, an award-winning coffee producer in El Salvador. In the beginning, everyone was apprehensive, but it's not rocket science, and we got to understand how to do it well pretty quickly.

For that reason, three of our first places at Cup of Excellence are honey processed Pacamara.

Jamie notes that honey processing is also becoming more popular in countries like Guatemala, Vietnam, Myanmar, Peru, and Uganda, underscoring its widespread appeal.

The New Normal in Specialty Coffee

As more countries began processing black, red, yellow, and white honey coffees at higher volumes, the global market quickly became saturated with them. With varying flavor profiles and mouthfeel, these coffees appealed to a wide range of consumers, allowing coffee shops and roasters to meet diverse demands.

Over time, honey processed coffees became standard offerings in the specialty coffee market. Once considered differentiated and even too funky, they no longer stood out as consumers sought more interesting and unique flavor experiences.

When we started our farm decades ago, we processed 90 percent washed coffees and only 10 percent non-washed, Jorge explains. Nowadays, it's the opposite; we do 80 percent non-washed and 20 percent washed because that's what consumers want.

The proliferation of experimental processing methods in recent years, most notably various types of controlled fermentation such as anaerobic and lactic fermentation, has captured some of honey processed coffee's market share. Offering even more complex, layered, and interesting flavor profiles, advanced and novel processing techniques have become more common in specialty coffee.

At the same time, standardization became a challenge for honey processed coffees.

The percentage of mucilage left intact, as well as fermentation and drying times, all vary, so what one producer creates as red might be another producer's yellow or black, Jamie explains. We have producers that offer red honey coffees, but the percentage of mucilage and fermentation and drying times are all different, so the colors cover a broad spectrum.

White honey coffees, in particular, can be close to washed coffees, but how producers develop them varies, he adds. They can be pulped with 5 percent mucilage left on, or a short drying time with 90 percent of the mucilage intact.

Looking Ahead

Despite being considered a standard processing method by many, producers in Costa Rica and beyond continue to innovate with honey processed coffees.

While some use the processing method as a base to build on further flavor development, others have created new types of honey processed coffees. Pink, orange, and golden honeys have appeared in specialty coffee shops and roasters, although the exact mucilage percentages and fermentation and drying times are unknown. This drives innovation but also complicates standardization.

Honey processing has always been about different variations. In the beginning, people thought you could only do honey, natural, and washed coffees, but you can do so many variations, Jorge says. That is what's so interesting and special about it.

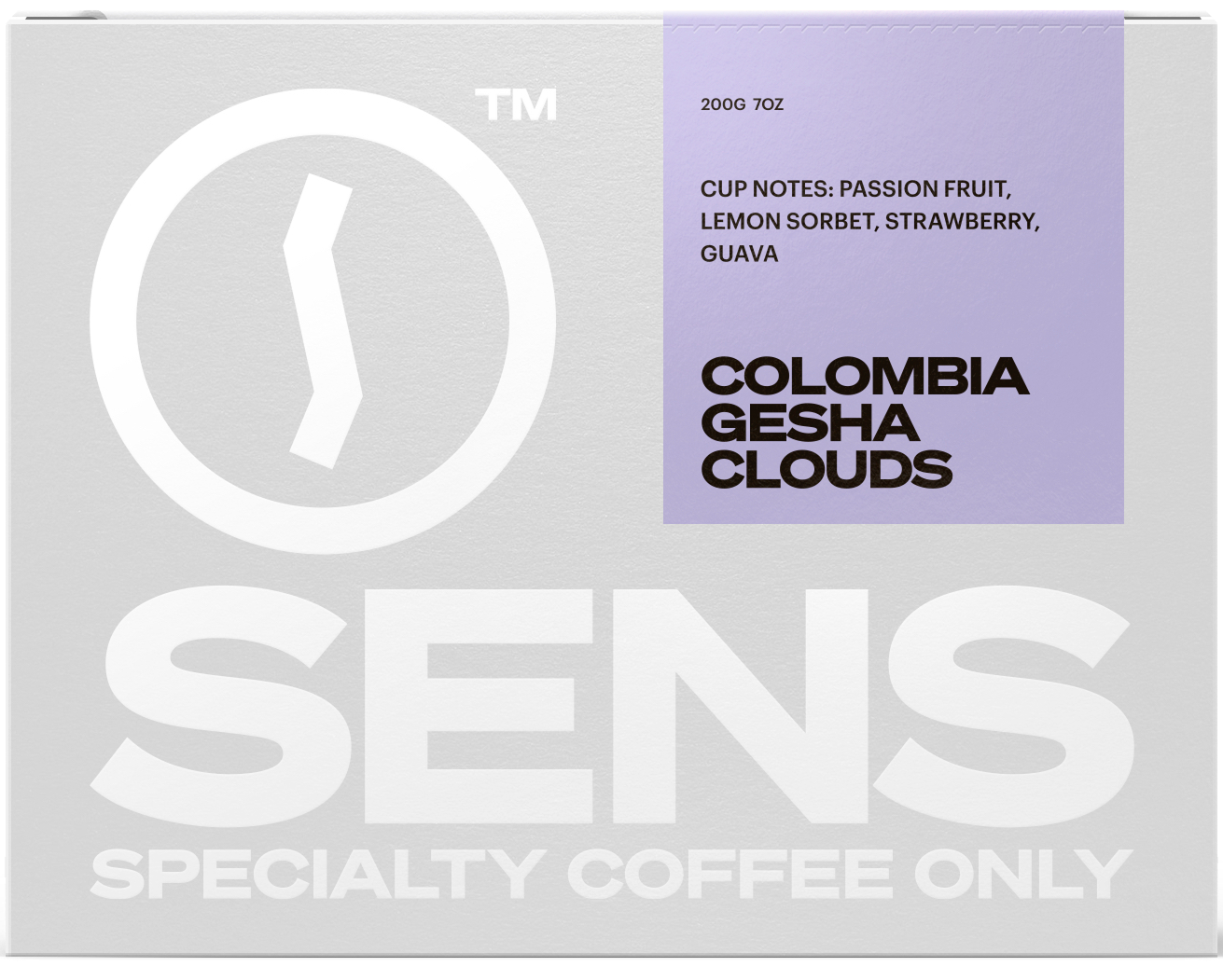

There's no specific variety that works best, too. Pacamaras work well as honey processed coffees, and Geshas, when done well without too much fermentation, taste amazing. It's a matter of craftsmanship.

There is immense value in honey processing, especially in producing countries where access to water is scarce. For this reason, producers will continue to leverage this processing method, whether on its own or as a foundation for further innovation.